Why Burnout Is a Spiritual Crisis, Not a Time-Management Problem

Burnout is usually treated as a logistical failure.

Too many meetings. Too little sleep. Poor boundaries. Inadequate delegation. The proposed solutions follow naturally: optimize your calendar, reduce your workload, take a vacation, download a better productivity app. Burnout is framed as a resource-allocation problem, a miscalculation of energy inputs and outputs.

History suggests something deeper.

Burnout has appeared in every era where human beings were asked to live in sustained contradiction with their inner values. Long before modern corporations and digital overload, philosophers and mystics described states of exhaustion that did not originate in the body, but in the soul. What we now label burnout was once understood as disorientation—a loss of meaning disguised as fatigue.

The modern world tends to pathologize burnout individually. The exhausted leader is told they are not resilient enough, not disciplined enough, not efficient enough. Rarely do we ask whether the way of life itself is coherent. Rarely do we question whether constant striving without inward alignment is sustainable at all.

Burnout is not caused by effort alone. It is caused by effort divorced from meaning.

Ancient thinkers recognized this distinction clearly. Aristotle, writing in fourth-century BCE Greece, distinguished between activity that fulfills one’s nature and activity that merely consumes energy. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he argued that human flourishing (eudaimonia) arises not from constant action, but from action aligned with purpose and virtue. Labor that contradicts one’s inner telos produces not satisfaction, but depletion.

This insight reappears in religious traditions across cultures. In early Christian monasticism, burnout was known as acedia—a state of spiritual desolation marked by restlessness, apathy, and fatigue. Acedia was not laziness. It was a profound loss of orientation, a sense that one’s actions no longer mattered. Monks described feeling exhausted even while physically idle, and restless even while surrounded by stillness.

The Desert Fathers of the fourth century CE treated acedia as a crisis of meaning, not discipline. Their remedies were not efficiency hacks, but realignment: prayer, solitude, honest self-examination, and reconnection with purpose. They understood that exhaustion of the soul cannot be cured by rest alone.

The same pattern appears in Eastern philosophy. In the Bhagavad Gita, composed roughly between the fifth and second centuries BCE, the warrior Arjuna experiences paralysis not because he lacks skill or courage, but because his actions have lost moral clarity. Krishna does not offer him a better battle plan. He restores Arjuna’s sense of alignment—his understanding of duty, purpose, and right action. Only then does energy return.

Burnout emerges when action continues after meaning has collapsed.

Modern neuroscience supports this ancient intuition. Studies on motivation show that effort driven by intrinsic values produces vitality, while effort driven by external pressure produces fatigue—even when workloads are identical. When leaders operate primarily from obligation, fear, or identity maintenance, their nervous systems remain in chronic stress response. Over time, this becomes exhaustion.

This explains why high-performing individuals often burn out after achieving success. The external goals have been met, but the internal narrative has not evolved. The leader continues to operate from a survival or validation mindset long after those strategies have become obsolete. Energy drains because the psyche is no longer invested.

In leadership contexts, this manifests as a peculiar fatigue that no amount of rest resolves. Vacations provide temporary relief, but the exhaustion returns upon re-entry. The problem is not workload; it is orientation. The leader is expending energy in service of an outdated identity.

History offers many examples of figures who reached this threshold.

In the late Roman Republic, elite statesmen often experienced profound disillusionment after attaining power. Cicero, the Roman orator and philosopher of the first century BCE, wrote extensively about the emptiness of political ambition divorced from virtue. Despite immense success, he oscillated between engagement and withdrawal, struggling to reconcile public life with inner integrity. His fatigue was existential, not physical.

The same pattern appears in modern corporate life. Executives describe feeling “done” long before retirement age—not because they are incapable, but because the meaning structure that once fueled them has eroded. They continue to perform, but the work no longer nourishes.

Burnout, in this sense, is a signal—not a failure.

It signals that a transition is required. Not necessarily a career change, but a shift in the inner architecture of motivation. Leaders must move from extraction to contribution, from proving to serving, from accumulation to integration.

This transition is rarely encouraged by contemporary culture, which equates slowing down with falling behind. Yet every wisdom tradition emphasizes cycles of effort and renewal. Nothing in nature grows endlessly. Seasons exist not to limit life, but to sustain it.

The industrial mindset treats humans as machines. Machines can run continuously if properly maintained. Humans cannot. We require meaning as fuel. Without it, efficiency becomes corrosive.

Burnout intensifies when leaders suppress this signal and attempt to solve it mechanically. They optimize schedules while ignoring conscience. They delegate tasks while avoiding deeper questions. The result is often a more efficient path to deeper exhaustion.

The alternative is to treat burnout as an initiation.

An initiation does not remove difficulty; it reframes it. The leader begins to ask different questions: What am I actually serving? Which parts of my work are aligned with my values, and which are performative? Where am I expending energy to maintain an image rather than fulfill a purpose?

These questions are uncomfortable precisely because they threaten existing identities. Yet history suggests that leaders who avoid them pay a higher price later—often in health, relationships, or ethical compromise.

Burnout becomes catastrophic when ignored. It becomes transformative when understood.

The modern world does not need more resilient leaders in the narrow sense. It needs leaders willing to undergo the deeper realignment that burnout demands. Those who heed this call often emerge with greater clarity, compassion, and authority—not because they work harder, but because they work from coherence.

Burnout is not the end of leadership. It is the end of a particular way of leading.

When burnout is understood as a signal rather than a defect, the leader’s relationship to exhaustion changes fundamentally.

Instead of asking how to push through, the leader begins to ask what must be relinquished. Burnout is rarely asking for rest alone. It is asking for truth. It demands that the leader confront where their life has become misaligned with their deeper values, and where effort has replaced meaning as the primary motivator.

This is why burnout often intensifies when people attempt to “fix” it superficially. Time off helps, but only temporarily. Wellness programs soothe symptoms, but do not resolve the underlying contradiction. When the leader returns to the same internal posture—driven by fear, identity maintenance, or unconscious obligation—the exhaustion resumes.

The ancient world treated this moment with gravity.

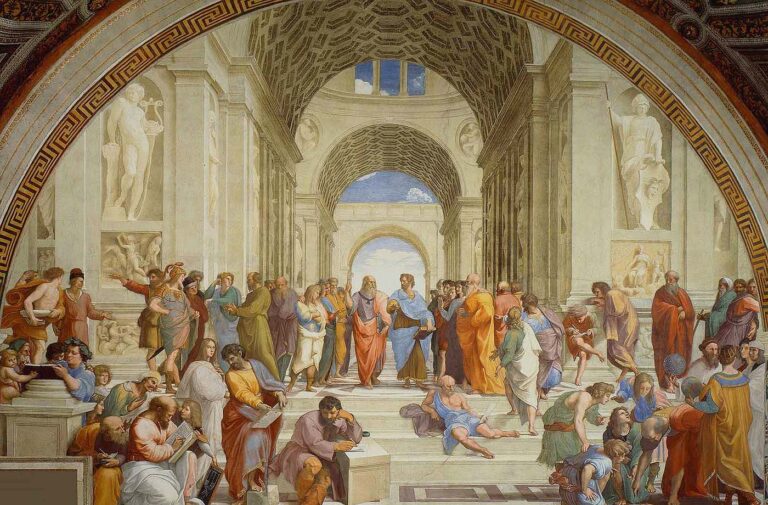

In the classical Greek tradition, periods of withdrawal were considered essential to philosophical and civic life. Plato’s Academy was not merely a school, but a space set apart from political urgency. Leaders were expected to step back from action periodically to reorient themselves toward truth. Without this withdrawal, action became unmoored from wisdom.

The same principle appears in Eastern traditions. In Taoism, articulated in texts like the Tao Te Ching, attributed to Laozi in the sixth century BCE, forced effort (wei) is contrasted with aligned action (wu wei). Burnout arises when one acts against the grain of reality, expending effort to sustain forms that no longer serve. Recovery occurs not through exertion, but through realignment.

Burnout, in this sense, is not failure—it is feedback.

Modern leaders often ignore this feedback because it threatens the narrative of control. To admit burnout as spiritual disorientation feels dangerous in cultures that equate leadership with invulnerability. Yet history suggests that leaders who refuse this reckoning tend to compensate through domination, distraction, or withdrawal.

Burnout unexamined leads to cynicism.

This cynicism manifests subtly at first. The leader becomes impatient with ideals they once championed. Conversations feel repetitive. Purpose statements ring hollow. People are seen as obstacles rather than participants. The work continues, but the heart is absent.

Unchecked, cynicism hardens into detachment. Leaders continue to perform, but no longer care deeply about outcomes beyond self-preservation. Ethical lines blur. Shortcuts appear reasonable. Burnout becomes moral erosion.

Ancient moral philosophers warned against this trajectory explicitly. Aristotle cautioned that habituated action without reflection leads not to virtue, but to vice. One may appear functional while gradually losing the capacity for ethical discernment. Burnout accelerates this process by numbing sensitivity.

The alternative path requires courage.

Leaders who treat burnout as an initiation allow it to dismantle outdated structures of meaning. This dismantling can feel destabilizing. Long-held ambitions lose their charge. External validation no longer satisfies. Familiar identities dissolve.

This is not a breakdown. It is a threshold.

In Jungian psychology dating from the early twentieth century, this stage is described as the confrontation with the shadow—the aspects of the self disowned in pursuit of a socially acceptable persona. Burnout often surfaces when the persona has been overextended for too long. Energy drains because the psyche can no longer sustain the split between who one appears to be and who one actually is.

Integration restores vitality.

When leaders allow themselves to acknowledge previously ignored values—creativity, service, truthfulness, spiritual inquiry—energy returns not as adrenaline, but as steadiness. Motivation shifts from compulsion to commitment. Work becomes expressive rather than extractive.

This does not require abandoning responsibility. Many leaders emerge from burnout not by leaving their roles, but by inhabiting them differently. They delegate more honestly. They stop overfunctioning. They allow others to step into responsibility rather than hoarding control.

This redistribution of agency is often the most visible sign of inner realignment.

Burnout also alters how leaders relate to time. Instead of viewing time as an enemy to be conquered, they begin to respect rhythm. Work and rest are no longer opposites, but complementary phases of a larger cycle. Productivity becomes sustainable because it is no longer fueled by depletion.

History offers striking examples of leaders who underwent such transitions.

In the late nineteenth century, Leo Tolstoy—the Russian novelist and moral thinker—experienced a profound spiritual crisis after achieving immense literary success. Despite fame and wealth, he fell into despair, questioning the meaning of his work and life. His crisis did not lead to withdrawal from society, but to radical reorientation. He turned toward ethical living, simplicity, and service. While controversial, this transformation infused his later writings with moral urgency that continues to influence readers worldwide.

Tolstoy’s burnout was not cured by rest. It was cured by alignment.

Modern neuroscience corroborates this transformation. When motivation aligns with intrinsic values, the nervous system shifts from chronic stress activation to regulated engagement. Leaders feel energized not because demands diminish, but because effort is no longer resisted internally. The body recognizes coherence.

Burnout also sharpens discernment.

Leaders emerging from burnout often develop a refined sensitivity to unnecessary complexity. They simplify structures, clarify priorities, and eliminate performative work. This simplification is not minimalism for its own sake; it is a response to the recognition that energy is finite and sacred.

Such leaders tend to become more compassionate—not sentimentally, but practically. They understand suffering not as weakness, but as a universal human condition. This understanding improves decision-making. Policies become humane. Expectations become realistic. Accountability remains, but it is tempered by understanding.

Burnout, then, is not opposed to leadership maturity. It is one of its gateways.

The tragedy is not that leaders burn out. The tragedy is that so few are supported in navigating what burnout asks of them. It is treated as an inconvenience rather than a call to transformation.

History suggests that civilizations stagnate when leaders suppress this call. Renewal occurs when leaders allow exhaustion to teach them something essential about power, purpose, and responsibility.

Burnout strips away illusion. What remains is truth.

What ultimately distinguishes leaders who emerge strengthened from burnout is not technique, but honesty.

They stop pretending that exhaustion is accidental. They recognize it as the natural consequence of living out of alignment for too long. This recognition dissolves shame. Burnout is no longer evidence of inadequacy; it becomes evidence of awareness trying to reassert itself.

At this point, leadership shifts from endurance to embodiment.

Embodied leadership does not mean emotional display or constant vulnerability. It means that decisions arise from the whole person rather than from a fragmented self. Thought, emotion, and values are integrated. Action feels congruent rather than forced. The leader is no longer divided against themselves.

This integration is what allows leaders to remain effective without being depleted.

History’s most grounded leaders shared this quality. They were not perpetually intense. They did not confuse seriousness with tension. Their presence carried steadiness rather than urgency. People trusted them not because they were flawless, but because they were real.

In the Zen tradition, which developed in China and Japan over many centuries, burnout would be described as acting from ego rather than from awareness. The remedy was not withdrawal from responsibility, but presence within it. Zen masters taught that exhaustion arises when one resists the moment—when one strives to impose outcomes rather than respond to reality.

This principle applies directly to leadership.

Leaders burn out when they attempt to control what cannot be controlled: perception, approval, permanence. They recover when they focus on what is theirs to steward: intention, attention, and action aligned with conscience.

This shift also changes how leaders relate to success.

When burnout is integrated, success no longer feels like a demand to keep proving oneself. It becomes a byproduct of aligned effort. Failure, likewise, loses its existential threat. It is painful, but not annihilating. The leader’s sense of worth is no longer contingent on outcomes.

This inner freedom is what allows leaders to take genuine risks—ethical risks, creative risks, human risks. Ironically, burnout often precedes the most courageous phases of leadership precisely because it dismantles false incentives.

Leaders who have burned out and returned consciously tend to simplify their lives. They reduce unnecessary commitments. They speak more plainly. They prioritize depth over breadth. This simplification is not retreat; it is refinement.

The philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, writing in nineteenth-century Denmark, warned that despair arises when one tries to be what one is not. Burnout is often the bodily manifestation of this despair. Recovery occurs when leaders allow themselves to become who they already are rather than who they are expected to be.

Modern organizational research increasingly echoes this insight. Leaders who operate from authentic values exhibit greater resilience, foster stronger cultures, and sustain performance over time. Authenticity is not a branding exercise; it is a structural condition for vitality.

Burnout also redefines ambition.

Before burnout, ambition often centers on accumulation: status, influence, recognition. After burnout, ambition tends to reorient toward contribution: what impact remains when the self recedes? This is not moral superiority. It is clarity. The leader recognizes that fulfillment arises not from having more, but from being aligned with something meaningful.

This reorientation mirrors ancient understandings of vocation. In medieval thought, vocation was not chosen to maximize pleasure or prestige. It was discerned as a calling—an obligation to serve where one’s gifts met the world’s needs. Burnout often marks the moment when leaders realize they have outgrown a purely instrumental relationship to work.

Importantly, this does not mean abandoning excellence. On the contrary, leaders who integrate burnout often become more effective because they are no longer scattered. Their energy is concentrated. Their decisions are cleaner. Their presence steadier.

Organizations led by such individuals feel different. There is less performative urgency. Fewer crises manufactured by misalignment. More space for thought. More respect for human limits.

Burnout, properly understood, is therefore not a personal inconvenience but a cultural signal.

It reveals where systems demand constant output without providing meaning, where leadership roles reward sacrifice without offering integration. Treating burnout solely as an individual pathology allows organizations to avoid examining these deeper issues.

History suggests that societies evolve when enough leaders heed such signals.

The industrial age rewarded endurance. The emerging age requires coherence. Complexity has outpaced brute force. Leaders must navigate ambiguity, moral pluralism, and rapid change. Burnout becomes inevitable if they attempt to meet these demands with outdated inner architectures.

The leaders who thrive in this environment will not be those with the best time-management systems, but those with the deepest alignment.

Burnout does not ask leaders to stop leading. It asks them to lead differently.

It invites them to relinquish identities built on proving and control, and to inhabit roles grounded in presence and purpose. This invitation is uncomfortable, but it is also liberating. Leaders who accept it often discover a quieter, more sustainable form of authority—one that does not consume them.

In this sense, burnout is not an interruption to leadership. It is a crossroads.

Those who ignore it often return to the same patterns until collapse forces change. Those who listen may emerge transformed—not less ambitious, but more whole.

The modern world urgently needs such leaders. Not because they work less, but because they work from coherence rather than compulsion. Not because they avoid responsibility, but because they carry it without losing themselves.

Burnout is not the enemy of leadership.

Unexamined burnout is.