What Happens After You Win? History’s Most Powerful Figures Faced This Question Too

Winning has always been humanity’s most celebrated achievement—and its most quietly destabilizing one.

Modern culture devotes enormous energy to teaching people how to win. We study strategy, competitive advantage, performance psychology, and optimization systems. We celebrate those who reach the summit, amplify their stories, and dissect their methods. Winning is framed as both validation and destination. Once attained, it is assumed to confer satisfaction, security, and meaning.

History suggests otherwise.

Across eras and civilizations, the moment after victory has often proven more perilous than the struggle that preceded it. Empires falter not in ascent but in triumph. Leaders unravel not while striving, but after they have secured what they sought. The question “What happens after you win?” has confronted humanity’s most powerful figures again and again—and their answers have shaped the fate of nations.

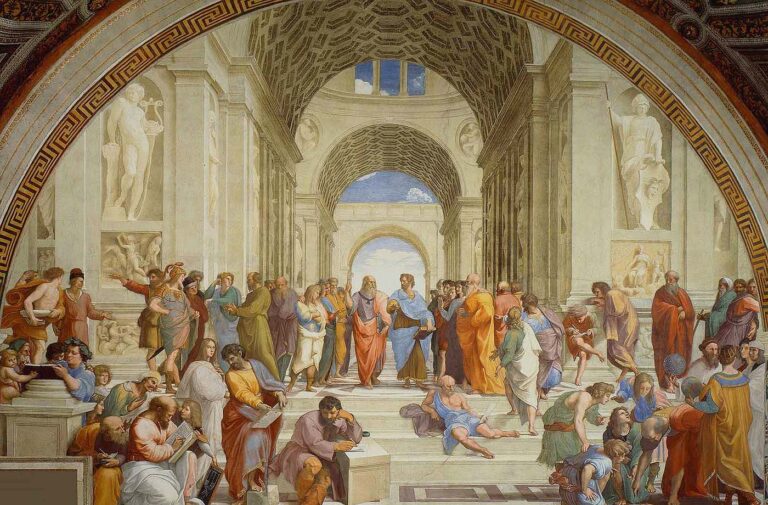

Ancient historians understood this pattern with sobering clarity. In the fifth century BCE, Herodotus—the Greek historian often called the “father of history”—watched how success can intoxicate rulers and nations. In his Histories, expansion produces confidence; confidence hardens into presumption; presumption invites overreach. The Greeks had a moral vocabulary for the arc of victory: koros, the surfeit that follows excess; hubris, the arrogant blindness that ignores limits; and nemesis, the corrective force that arrives when limits are violated. This was not simply mythology. It was a way of speaking about the psychological and civic deterioration that often follows unexamined success.

Thucydides—the Athenian general and historian writing later in the fifth century BCE—offered a harsher, more political version of the same lesson in his History of the Peloponnesian War. Athens did not collapse because it lacked intelligence, bravery, or resources; it collapsed because success distorted judgment. Victory created a kind of moral anesthesia. Over time, the Athenians treated restraint as weakness and prudence as hesitation. They became persuaded that power justified itself. The disastrous Sicilian Expedition was not merely a tactical error—it was the predictable outcome of a city that had begun to believe its own narrative of inevitability.

This is the first hidden danger after victory: the inner discipline that struggle naturally provides is suddenly gone.

During ascent, the world pushes back. Resistance compels adaptation. Obstacles force humility—at least temporarily. The climb disciplines the ego because the ego is repeatedly reminded it is not omnipotent. But victory removes friction. What remains is the raw material of the leader’s inner life: unexamined hunger, unresolved fear, and the subtle belief that winning proves worth. In the climb, the ego is busy; after the summit, it becomes loud.

Consider Alexander the Great, the Macedonian king of the fourth century BCE who conquered vast territories by the age of thirty. His victories were astonishing: Greece, Persia, Egypt, and deep into Central Asia. Yet ancient sources, including the well-known biographer Plutarch, depict a man who grew increasingly isolated and volatile as the external struggle diminished. Court politics intensified. Suspicion spread. The drive that had once been strategic began to look existential, as if conquest had become necessary to keep meaning alive. When there are no more enemies to defeat, the restless parts of the self can become the enemy.

Alexander did not fail because he lacked power. He became vulnerable because power was no longer balanced by resistance, and victory offered no map for the next phase of inner development.

Julius Caesar offers another instructive case, in the first century BCE, during the final crisis of the Roman Republic. Caesar’s victories in Gaul made him the most celebrated commander of his generation. His crossing of the Rubicon was the moment the pursuit of success became openly incompatible with the existing moral order. Yet even after the civil war, even after he effectively “won,” Rome had no stable framework for a man who had already won. The Republic’s institutions were built to prevent a single figure from consolidating permanent supremacy. Caesar’s victory was therefore not only personal; it was structural. It forced a civilization to face the question: what comes after one person becomes too successful?

The answer, in this case, was instability. Legitimacy could not keep pace with power. The demand for security increased. The temptation toward autocracy intensified. And Caesar’s assassination—whether viewed as defense of republican ideals or as desperation—reveals how victory can destabilize the very world it was meant to secure.

This is the second danger after you win: the environment changes, and people change with it.

Winning rearranges the social field. It amplifies admiration and resentment simultaneously. It creates dependents, rivals, and performers. It invites flattery. It narrows feedback. And as feedback narrows, judgment degrades. The leader still believes they are seeing reality, but they are increasingly seeing a curated version of it—filtered through the incentives of those around them.

Ancient wisdom traditions addressed this not only politically but psychologically. The Stoic philosophers of the early Roman Empire wrote for people who had already “arrived” by conventional standards—senators, merchants, administrators, and rulers. Seneca, a Roman statesman and adviser to Emperor Nero in the first century CE, warns in Letters from a Stoic that prosperity tests character more severely than adversity. Adversity is an honest adversary: it announces itself, and it can be met with courage. Prosperity seduces quietly. It turns the mind outward. It encourages entitlement. It persuades a person that their comfort is evidence of their correctness.

This is why Seneca repeatedly returns to inner freedom: the capacity to remain steady regardless of fortune’s fluctuations. He is not teaching resignation; he is teaching leadership of the self. Without that leadership, outer success becomes the very condition that erodes inner integrity.

Marcus Aurelius—Roman emperor in the second century CE—used his private notes in his Meditations to keep himself awake. He returns again and again to impermanence, humility, and service. Praise is vapor. Status is borrowed. Power is temporary. These are not the reflections of a man who thinks victory is the end. They are the disciplines of a leader who understands that winning is the beginning of a more subtle test: whether the self can remain intact when the world stops resisting.

When the world no longer pushes back, self-deception grows easier. The leader may begin to confuse the role with the person, the applause with truth, the machinery of success with the meaning of life.

The third danger after you win is subtler still: identity hardens.

On the way up, you are allowed to be unfinished. You are “becoming.” After victory, the world expects you to “be.” Your story becomes fixed. Your persona becomes a product. And the self begins to serve the image. This is not confined to celebrities. It happens to executives, founders, partners, and senior leaders in quieter ways. The role begins to colonize the person. Curiosity narrows. Risk becomes threatening—not because the leader lacks courage, but because identity has become dependent on maintaining a particular kind of narrative.

This helps explain the restlessness many high achievers experience after crossing major thresholds. The restlessness is not ingratitude. It is not failure. It is the psyche signaling that the identity built for ascent is no longer sufficient for stewardship. Winning completes one narrative arc, but it also exposes the emptiness of living permanently inside that arc. If life becomes the repetition of the first win, the soul eventually revolts.

Ancient cultures often tried to protect victors from this trap through ritual humility. In Rome, the triumphal parade—at least in the tradition remembered by later writers—carried a reminder of mortality: memento mori, remember you must die. Literal or symbolic, the intent is unmistakable. Victory requires a counterweight. The leader must be reminded that success does not make one godlike; it makes one more responsible. The body is still mortal; the mind is still fallible; the moral order still matters.

Even in myth, victory without integration becomes dangerous. King Midas “wins” what he thinks he wants—gold—but the win reveals itself as curse. The myth is not a condemnation of desire; it is a warning about unexamined desire. The moment you get what you want is the moment you discover what you truly wanted. Some people wanted security. Some wanted admiration. Some wanted escape. Some wanted to feel worthy. Winning can deliver the outer object while leaving the inner need untouched, and that mismatch can become painful enough to force transformation.

Modern success culture rarely offers a mature framework for this phase. It encourages escalation: more goals, bigger targets, higher mountains. But history suggests that what is needed after you win is not always a higher peak. Sometimes it is a deeper horizon. The question is not “How do I keep winning?” but “What does winning ask of me now?” What responsibilities does it impose? What temptations does it amplify? What parts of me must be strengthened so that power does not outpace integrity?

The figures who faced this question and answered it well were rarely the most dazzling in their victory. They were the ones who learned to convert success into service, and power into authority. Those who answered it poorly often became cautionary tales: powerful, admired, and increasingly hollow. The difference between these paths is not luck. It is orientation. It is whether success is treated as an endpoint—or as an initiation into a more demanding form of responsibility.

Winning, then, is not a destination. It is a threshold.

History’s most enduring leaders understood this intuitively, even when their cultures lacked the language to articulate it clearly. Victory did not absolve them of discipline; it intensified the need for it. After winning, the struggle moved inward. The external enemy vanished, but the internal one — pride, fear, attachment — remained.

This inward struggle is precisely what modern success culture neglects to prepare leaders for. We invest heavily in teaching people how to compete, but almost nothing in teaching them how to hold success without being consumed by it. The result is a generation of leaders technically capable yet existentially unmoored, outwardly accomplished yet inwardly fatigued.

The danger is not that winning makes people arrogant. The deeper danger is that it makes them fragile. When identity becomes anchored to success, failure — or even stagnation — feels like annihilation. This fragility explains why some leaders double down on control when circumstances shift, clinging to authority rather than cultivating it. Power becomes defensive. Decision-making narrows. Creativity declines. The very qualities that enabled success are gradually replaced by rigidity.

Ancient political thinkers warned against this repeatedly. Polybius, the Greek historian writing in the second century BCE, described how political systems decay not because of external invasion, but because success erodes virtue. Prosperity weakens discipline; discipline gives way to indulgence; indulgence corrodes responsibility. Leadership becomes performative rather than principled.

The same pattern appears in religious texts, where victory often triggers moral testing. In the Hebrew Bible, kings who begin their reigns with humility frequently fall into corruption after consolidating power. Their downfall is rarely immediate. It unfolds gradually, as unchecked success dulls accountability. Authority gives way to entitlement.

What these traditions share is an understanding that power magnifies character. It does not create virtue or vice; it reveals and amplifies what is already present. Winning removes excuses. Once the external struggle is gone, leaders confront themselves without distraction. Some discover depth. Others discover emptiness.

Modern psychology confirms this insight. Studies on power suggest that it increases confidence while simultaneously reducing empathy if not consciously counterbalanced. When feedback becomes filtered and consequences delayed, leaders risk losing touch with lived reality. The internal compass that once guided decisions begins to drift.

This is why so many successful individuals experience a crisis not during hardship, but during comfort. The crisis is not ingratitude; it is misalignment. The life they built no longer matches the self that built it.

At this juncture, leaders face a choice. They can attempt to recreate the conditions of struggle — chasing new challenges, new markets, new adversaries — or they can undergo a deeper transition. The former extends the first mountain indefinitely. The latter marks the beginning of a second phase of leadership.

History favors the latter.

Leaders who navigated victory wisely tended to reinterpret success as stewardship rather than entitlement. They recognized that winning placed them in a position of heightened responsibility — not to their ego, but to others. This shift transforms leadership from conquest to care, from accumulation to transmission.

One of the clearest examples in modern history is George Washington, the eighteenth-century military leader and statesman during the founding of the United States. After winning the Revolutionary War, Washington possessed immense popular authority and could plausibly have assumed lifelong power. Instead, he resigned his commission and later stepped down after two presidential terms. His greatest act of leadership occurred not during victory, but after it. By relinquishing power voluntarily, he converted success into legitimacy. Authority replaced dominance.

This decision reverberated far beyond his lifetime. It set a precedent that shaped political culture for generations. Washington understood what many conquerors did not: that winning without restraint destroys the very order victory is meant to secure.

Similar patterns appear in corporate and institutional leadership, though often less visibly. Leaders who treat success as a trust rather than a trophy tend to invest in succession, culture, and long-term resilience. They ask not only “How do we grow?” but “What must endure?” Their influence outlasts their tenure because it is embedded rather than imposed.

The question “What happens after you win?” therefore becomes a diagnostic tool. How leaders answer it reveals their orientation toward power, identity, and meaning. Those who answer by escalating ambition alone risk repeating the same cycle at higher stakes. Those who answer by deepening responsibility step into a quieter, more enduring form of leadership.

This transition is rarely celebrated. It lacks the drama of conquest. It offers fewer external rewards. Yet history suggests it is the point at which leadership becomes truly consequential.

The modern world, saturated with metrics and momentum, often resists this slowing. Yet the crises of our time — social fragmentation, institutional distrust, ethical exhaustion — point unmistakably toward the need for leaders who can hold success without being hollowed by it. We do not lack winners. We lack stewards.

Winning, properly understood, is an initiation into stewardship.

Those who pass through it unchanged may accumulate power, but they will struggle to sustain authority. Those who allow victory to reorient them — toward humility, service, and coherence — may find that success finally acquires meaning.

History does not remember who won the most battles, amassed the greatest fortunes, or climbed the highest peaks. It remembers those who knew what to do after they had already won.

And it is this forgotten question — more than strategy, intelligence, or ambition — that separates transient success from lasting leadership.