From Warrior Kings to Servant Leaders – How Leadership Lost Its Soul (and How It Might Recover It)

For most of human history, leadership was forged in conflict.

The earliest leaders were not administrators or visionaries; they were warriors. Survival demanded strength, decisiveness, and the capacity to defend territory against rival groups. Authority emerged from the ability to protect and prevail. The warrior king stood at the center of early societies because survival itself depended on him.

Yet even in these earliest forms, leadership was never solely about force.

Across ancient cultures, the warrior was expected to embody more than martial prowess. He was bound by codes—honor, restraint, responsibility to the tribe. Strength without moral orientation was feared as much as weakness. Leadership was not simply the capacity to dominate, but the obligation to safeguard life, order, and meaning.

This dual expectation—power tempered by service—formed the soul of early leadership.

In ancient Mesopotamia, kings like Hammurabi (eighteenth century BCE) presented themselves not merely as conquerors, but as guardians of justice. The Code of Hammurabi framed authority as a responsibility to protect the vulnerable, uphold order, and align earthly rule with divine law. The king was powerful precisely because he was accountable—to the gods, to the law, and to the people.

Similarly, in ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was not just a ruler but a cosmic mediator. His role was to uphold ma’at—the principle of balance, truth, and harmony. Warfare was sometimes necessary, but leadership itself was conceived as a sacred duty to maintain order in both the visible and invisible worlds. Power divorced from harmony was considered catastrophic.

These early civilizations understood something modern leadership culture often forgets: authority must be rooted in alignment with something larger than the self.

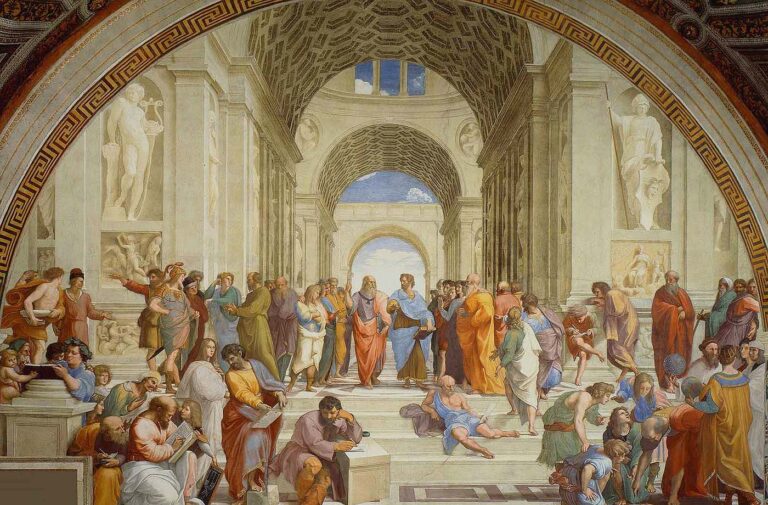

As societies evolved, so did the concept of leadership. The warrior king gave way, in some cultures, to philosopher-kings, lawgivers, and priest-rulers. Plato, writing in fourth-century BCE Athens, famously argued in The Republic that the ideal leader was not the strongest or the most ambitious, but the most wise. His philosopher-king ruled reluctantly, motivated not by desire for power but by duty to the good of the whole.

Plato’s vision was radical because it inverted the prevailing logic of dominance. Leadership, in his view, was not a reward but a burden. Those most fit to lead were often those least eager to do so. Power required inner discipline, not merely external control.

This theme reappears in religious traditions across the world. In the Hebrew scriptures, kings are repeatedly warned that their authority is conditional. They are shepherds, not owners. When they forget this—when they exploit rather than serve—the consequences are severe. Leadership is depicted as covenantal: a relationship grounded in responsibility, not entitlement.

The same inversion appears in early Christianity. Jesus of Nazareth, a first-century Jewish teacher, reframed leadership entirely: “Whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant.” This was not rhetorical humility. It was a direct challenge to the prevailing Roman model of hierarchical domination. Authority, in this vision, flowed upward from service rather than downward from force.

Islamic political thought similarly emphasized stewardship. Early caliphs were described as custodians rather than sovereigns. Leadership was a trust (amanah), not a possession. The ruler was accountable to God and community alike. Power existed to uphold justice, not to glorify the ruler.

Across these traditions, leadership retained a soul because it remained tethered to moral and spiritual responsibility.

The erosion of that soul began not with modernity, but with scale.

As empires expanded, leadership became increasingly abstract. Rulers governed territories they could not see, people they could not know, and consequences they would never directly experience. Bureaucracy emerged as a necessity. Systems replaced relationships. Efficiency replaced intimacy.

This was not inherently corrupting. Administration allowed civilizations to function at unprecedented scale. But something subtle shifted. Leadership became less personal and more procedural. Authority migrated from embodied presence to institutional role.

The Roman Empire illustrates this transition vividly. Early Roman leaders were citizen-soldiers, bound by shared sacrifice and civic duty. Over time, imperial administration grew vast and impersonal. Emperors became distant figures. Loyalty shifted from shared values to centralized power. The moral intimacy that once constrained authority eroded.

When leadership loses proximity, it risks losing empathy.

The medieval period attempted to recover spiritual grounding through the idea of divine kingship. Yet this often reinforced hierarchy rather than accountability. Power was sanctified, but not necessarily restrained. The ruler answered to God—but rarely to the people. The result was a brittle fusion of spiritual symbolism and political dominance.

By the early modern period, leadership increasingly secularized. The Enlightenment brought reason, rights, and constitutional governance—immense advances in human freedom. Yet it also accelerated a new reductionism. Leadership became managerial. Systems mattered more than souls. Rationality displaced wisdom. Efficiency became virtue.

The Industrial Revolution completed this transformation. Leaders were no longer warriors or sages; they were organizers of labor, capital, and production. Success was measured in output. Authority flowed from ownership and control. The human being became a unit of productivity.

In this context, leadership lost its inner dimension.

The twentieth century exposed the dangers of soulless leadership at scale. Totalitarian regimes demonstrated how efficient systems, stripped of ethical grounding, could mobilize entire populations toward destruction. These leaders were not chaotic. They were organized, disciplined, and methodical. Their failure was not inefficiency, but moral blindness.

After these catastrophes, leadership theory attempted to reintroduce ethics, values, and emotional intelligence. Yet much of this effort remained superficial. Values were codified, not embodied. Ethics became compliance. Servant leadership was discussed, but rarely practiced beyond rhetoric.

The modern corporate leader often inhabits a paradoxical position: immense influence combined with profound disconnection. Decisions affect thousands, sometimes millions, yet are mediated through spreadsheets, dashboards, and abstractions. The human cost is often invisible. Leadership becomes lonely, performative, and anxious.

This is where the soul of leadership goes missing—not through malice, but through disembodiment.

To lose the soul of leadership is not to become cruel; it is to become disconnected from meaning. Leaders may still be competent, even benevolent, but something essential is absent. Authority becomes positional rather than relational. Influence becomes transactional rather than transformational.

The rise of “servant leadership” language in recent decades reflects an intuitive attempt to correct this imbalance. Yet the term is often misunderstood. Servant leadership is not about self-effacement or managerial kindness. It is about orientation. The leader asks not “How do I extract value?” but “What does this role require of me in service to the whole?”

This orientation demands inner work.

A leader cannot serve authentically without confronting their own hunger for validation, control, and certainty. Service without self-awareness becomes martyrdom or manipulation. True service arises from coherence between values and action.

Recovering the soul of leadership, then, is not a return to nostalgia. It is not a rejection of systems, efficiency, or modern complexity. It is an integration. The warrior’s courage must be joined with the servant’s humility. The strategist’s intelligence must be balanced by the steward’s care.

History suggests that leadership evolves not in straight lines, but in cycles. Periods of dominance give way to periods of reflection. When power becomes excessive, cultures rediscover restraint. When leadership becomes soulless, humanity seeks renewal.

The question before us now is whether this renewal will be conscious—or forced.

Leadership recovers its soul not through sentiment, but through initiation.

In traditional cultures, leadership was never merely assigned; it was earned through transformation. Before one was entrusted with authority over others, one was required to confront oneself. The warrior did not simply train the body. He was trained to master fear, temper aggression, and submit to codes that limited his own power. The elder did not simply age into authority. He demonstrated discernment, patience, and the capacity to hold complexity without collapsing into certainty.

Modern leadership culture has largely abandoned this initiatory dimension.

Today, leaders often ascend through performance metrics, credentials, or financial success. These are not trivial achievements, but they do not, on their own, prepare a person to wield influence wisely. They refine skills without necessarily maturing character. As a result, individuals are placed in positions of immense responsibility without undergoing the inner recalibration such responsibility requires.

This gap explains why leadership roles so often become psychologically destabilizing. The position expands faster than the person. The role demands coherence, but the inner life remains fragmented. The leader becomes reactive, defensive, or compulsively controlling—not because they are unethical, but because they are unprepared.

Historically, this problem was addressed through ritualized ordeal.

Among Indigenous societies, future leaders were often subjected to periods of isolation, fasting, or exposure to hardship. These experiences were not punitive. They were designed to dissolve egoic certainties and cultivate humility. One returned not inflated, but grounded. Authority emerged from self-knowledge rather than dominance.

Even in more centralized civilizations, echoes of this practice persisted. Medieval monastic orders required years of discipline before entrusting members with responsibility. Apprenticeship systems in craft guilds emphasized patience and submission to mastery before independence was granted. Leadership was framed as a state of being, not merely a function.

The erosion of these formative processes coincided with the rise of mechanized power.

As societies industrialized, leadership became increasingly instrumental. The leader was valued for output, speed, and control. Reflection was reframed as inefficiency. Inner development was privatized or ignored altogether. What mattered was execution.

Yet something essential was lost in this transition.

Without inner grounding, leadership becomes brittle. When circumstances change—as they inevitably do—the leader lacks the resilience to adapt without panic. Authority hardens into rigidity. Power becomes defensive. The leader’s primary concern shifts from stewardship to survival of status.

This is where servant leadership is often misunderstood.

Servant leadership does not mean the abdication of authority. It means the transformation of its source. Instead of drawing legitimacy from position alone, the leader draws it from trust. Instead of enforcing compliance, the leader cultivates commitment. This requires presence, self-regulation, and the willingness to place the integrity of the whole above personal advantage.

These capacities cannot be improvised under pressure. They must be cultivated long before they are tested.

The historical figures most associated with servant leadership were not passive idealists. They were individuals who had confronted suffering, limitation, and moral complexity directly. Their authority was credible because it was costly. It had been earned through sacrifice, restraint, and the relinquishment of simpler forms of power.

Nelson Mandela, emerging from twenty-seven years of imprisonment in South Africa in the late twentieth century, exemplified this transformation. His leadership after apartheid was not an expression of weakness, but of mastery. He understood that revenge would fracture the fragile future of the nation. Reconciliation, though slower and less emotionally satisfying, preserved the possibility of shared legitimacy. This choice required extraordinary inner discipline.

Mandela’s authority did not derive from efficiency. It derived from coherence between his inner convictions and his outward actions.

This coherence is what modern leaders often lack, not because they are immoral, but because they are fragmented. Their public persona diverges from their private experience. Decisions are made from pressure rather than clarity. Over time, this dissonance erodes trust—both externally and internally.

Psychology offers a clear explanation for this erosion. Sustained cognitive dissonance produces stress, fatigue, and emotional withdrawal. Leaders may continue to function, but they no longer feel alive in their role. The soul recedes when action consistently violates inner truth.

Servant leadership restores alignment.

When leaders act from a place of coherence, decisions carry a different quality. Even difficult actions—terminations, restructurings, strategic withdrawals—are experienced as clean rather than corrosive. They do not leave residue. The leader sleeps at night not because choices were easy, but because they were honest.

This is why awareness practices—reflection, contemplation, embodied attention—are not luxuries for leaders. They are maintenance for the instrument through which leadership operates: the self.

Ancient philosophies recognized this explicitly. Stoicism, developed in Hellenistic Greece and later adopted by Roman leaders, treated self-mastery as the foundation of authority. Epictetus, a former slave turned philosopher in the first century CE, taught that the only true power lay in governing one’s own responses. External control was unreliable; inner freedom was sovereign.

This philosophy appealed to leaders precisely because it offered stability in uncertain environments. A leader anchored internally could navigate chaos without becoming chaotic. Awareness was not abstraction; it was strategy.

The modern equivalent of this discipline is still emerging. Leadership development programs speak of mindfulness, emotional intelligence, and resilience, but often strip them of their existential depth. Techniques are taught without transformation. Tools are adopted without surrender.

What history suggests is that leadership regains its soul only when leaders are willing to be changed by the role itself.

This change is not cosmetic. It involves the dismantling of certain identities: the need to be admired, the fantasy of control, the belief that worth is conditional on success. As these illusions fall away, something quieter and more stable emerges. The leader becomes less reactive, more receptive. Authority softens without weakening.

It is at this point that leadership ceases to be performative and becomes generative.