The Forgotten Difference Between Power and Authority — A Lesson Modern Leadership Has Ignored

Modern leadership discourse is saturated with the language of power. We speak of power structures, power dynamics, power imbalances, power moves, and power players. Leadership programmes promise to teach influence, leverage, control, and strategic dominance. Organisational charts map where power sits; performance systems reward those who exercise it effectively. In many contemporary contexts, power has become synonymous with leadership itself.

Yet something essential has been lost.

Despite unprecedented access to power — technological, financial, organisational — many leaders experience a quiet unease. They achieve what previous generations could scarcely imagine, yet feel increasingly isolated, mistrusted, or hollow. Teams comply but disengage. Institutions function but fail to inspire. Authority, once assumed to accompany power, no longer follows automatically.

This is not a new phenomenon. History has seen it before, and it has never ended well.

The mistake lies in a fundamental confusion: power and authority are not the same thing. They never were. Civilizations that failed to distinguish between them eventually discovered — often painfully — that power can compel obedience, but authority alone sustains legitimacy.

Power can be seized. Authority must be recognized.

Power enforces outcomes. Authority invites assent.

Power operates externally. Authority works inwardly, shaping trust, meaning, and moral alignment.

These distinctions are not abstract. They shape how leadership is experienced at every level, from the boardroom to the battlefield, from the polis to the corporation. When power outpaces authority, leadership becomes brittle. When authority anchors power, leadership becomes durable.

Ancient thinkers understood this intuitively. Modern systems, by contrast, have largely forgotten it.

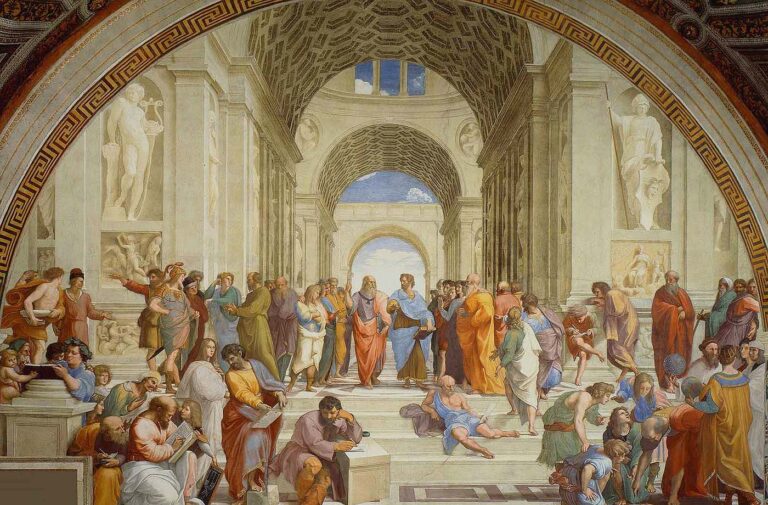

The earliest sustained examination of this distinction appears in ancient Greece. Plato, writing in The Republic, was preoccupied with the dangers of power unmoored from wisdom. His critique of tyranny is not merely a critique of cruelty or excess; it is a critique of illegitimacy. The tyrant governs by force and manipulation, driven by appetite rather than reason. He possesses immense power, yet lacks authority because his rule is not oriented toward the Good.

Plato’s proposed alternative — the philosopher-king — is often dismissed as idealistic or impractical. Yet the deeper insight remains relevant: leadership acquires authority when it is grounded in truth, justice, and self-mastery. Without these, power corrodes both ruler and ruled.

Aristotle refined this insight with characteristic realism. In Politics, he distinguishes between regimes that govern for the common good and those that govern for private interest. The former possess legitimacy; the latter merely exercise dominance. Authority, for Aristotle, arises when leadership is animated by virtue (arete) and guided by practical wisdom (phronesis). A ruler may command obedience through fear or law, but unless his rule is perceived as just, it will remain unstable.

Crucially, Aristotle recognized that authority is relational. It exists not solely in the leader, but in the relationship between leader and community. It depends on recognition, trust, and shared moral horizons. Where these erode, power persists only through coercion — a costly and ultimately unsustainable strategy.

The Roman world inherited these ideas and gave them linguistic precision. Romans distinguished sharply between imperium and auctoritas. Imperium referred to formal power: the legal right to command, punish, and enforce. Auctoritas, by contrast, referred to moral weight, credibility, and earned legitimacy. One could be granted imperium by office, but auctoritas had to be cultivated over time.

Cicero, writing during the final years of the Roman Republic, warned repeatedly that the erosion of auctoritas would doom the state. In De Officiis, he argued that leadership divorced from ethical responsibility becomes predatory, even when clothed in legal authority. Roman senators, elders, and statesmen often wielded enormous influence precisely because of their auctoritas, despite lacking direct command.

As the Republic decayed and the Empire consolidated power, this balance collapsed. Emperors accumulated vast imperium while systematically hollowing out auctoritas. Authority was replaced by spectacle, intimidation, and loyalty enforced through fear. Rome did not fall because it lacked power; it fell because authority had become performative and empty.

This pattern recurs across cultures.

In ancient China, Confucian philosophy articulated the concept of the “Mandate of Heaven.” A ruler’s legitimacy depended not on conquest or heredity alone, but on moral conduct and benevolent governance. Authority was conditional. When rulers governed unjustly, lost the trust of the people, or acted with cruelty, the mandate was considered withdrawn.

This was not mere superstition. It was a sophisticated political insight: leadership legitimacy rests on lived moral experience. When authority evaporates, power fractures. Rebellion, instability, and decline follow.

Religious traditions deepen this understanding further. In the Hebrew scriptures, kings are judged relentlessly — not by military success, but by fidelity to justice and covenant. Prophets, who possessed no formal power, nonetheless wielded immense authority through moral clarity. Their words endured precisely because they could not be enforced.

Early Christian thinkers carried this distinction into late antiquity. Augustine, in The City of God, argued that earthly power governs bodies, but authority governs conscience. When rulers attempt to dominate conscience, they exceed their mandate and corrupt themselves. Thomas Aquinas later synthesized Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology, asserting that authority arises when human law aligns with natural law — reason ordered toward the common good.

Across these traditions, authority emerges as inseparable from ethical alignment. It cannot be reduced to efficiency, output, or control. It is rooted in coherence between inner intention and outer action.

Modern leadership culture, however, developed along a different trajectory.

The rise of the modern state, the industrial revolution, and bureaucratic expansion reframed leadership as a technical function. Max Weber famously described this shift toward rational-legal authority — authority derived from rules, procedures, and roles rather than personal virtue or tradition. This transformation enabled scale, predictability, and organisational efficiency on an unprecedented level.

But it also stripped authority of its moral and existential dimensions.

In bureaucratic systems, authority is assumed to flow automatically from position. If one occupies the role, authority is presumed. If one meets targets, legitimacy is secured. Ethical questions are externalized into compliance frameworks and legal departments. Leadership becomes a matter of function rather than formation.

For a time, this model delivered extraordinary results. But its limitations are now increasingly visible. People obey systems they no longer trust. Leaders perform roles they no longer believe in. Power multiplies while authority thins — a tension at the heart of contemporary leadership malaise.

Yet even within modernity, the erosion of authority has not gone unnoticed. It has simply been misdiagnosed.

Contemporary leadership literature frequently identifies a “trust deficit,” an “engagement crisis,” or a “meaning gap,” proposing remedies in the form of improved communication, transparency initiatives, or cultural interventions. These responses are not wrong, but they are incomplete. They treat symptoms rather than causes. The deeper issue is not that leaders lack skill, but that leadership itself has been hollowed out of its moral centre.

Hannah Arendt, the German’American philosopher and influential political theorist of the last century, articulated this with striking clarity in her essay On Violence. She argued that power and authority are fundamentally different phenomena, and that violence — including institutional coercion — emerges precisely when authority has already begun to collapse. Authority, in her analysis, is what stabilizes power over time. When authority erodes, power becomes brittle, increasingly dependent on enforcement, surveillance, and spectacle.

This insight is particularly relevant to modern organizations. When leaders feel compelled to constantly assert their position, reinforce hierarchy, or justify decisions through force of mandate rather than shared purpose, authority has already been lost. Power may still function, but it does so at escalating psychological and social cost.

We recognize this intuitively. We have all encountered leaders who possess formal power yet inspire no loyalty, and others who command trust without issuing orders. The difference lies not in personality or charisma, but in coherence. Leaders with authority are aligned — internally and externally. Their actions correspond to their stated values. Their ambition serves something beyond self-advancement. Their presence conveys steadiness rather than urgency.

Authority, in this sense, is not performed. It is embodied.

This embodiment begins inwardly. Unlike power, which is external and positional, authority is inseparable from self-governance. One cannot credibly lead others without having first confronted one’s own motivations, fears, and contradictions. Ancient traditions understood this well. Plato insisted that rulers must master their own appetites before governing others. Confucius emphasised self-cultivation as the foundation of social harmony. Christian monastic traditions required leaders to undergo prolonged formation before assuming responsibility.

Modern leadership culture reverses this sequence. Individuals are elevated rapidly, rewarded for performance, and burdened with power long before inner alignment has been established. Development, if it occurs at all, is retrofitted after authority has already been assumed. This inversion produces leaders who are competent but brittle, successful yet insecure, influential yet inwardly divided.

The result is a subtle but pervasive anxiety. Leaders sense that their legitimacy is fragile. They compensate by tightening control, accelerating decision-making, and amplifying performance signals. The organization becomes louder, faster, and more reactive — precisely because authority has thinned.

This anxiety is contagious. It transmits downward through systems, manifesting as burnout, disengagement, and quiet resistance. People comply, but do not commit. They execute tasks, but withhold belief. Authority cannot be commanded; it must be granted. When it is not, power becomes a substitute — an increasingly poor one.

Recovering authority therefore requires a fundamental reorientation of leadership, one that begins not with strategy, but with purpose. The question shifts from “How do I lead effectively?” to “On what basis do I deserve to lead?” This is not a rhetorical question. It demands an honest reckoning with values, limits, and responsibility.

Authority grows where ambition is aligned with service. This does not mean abandoning ambition, but refining it. Ancient thinkers did not reject ambition; they sought to consecrate it. In Aristotle’s ethics, greatness of soul (megalopsychia) was a virtue, not a vice — but only when coupled with humility and justice. Ambition divorced from ethical orientation was considered destructive, not admirable.

Modern culture tends to moralise ambition only in terms of outcome. If success is achieved, ambition is justified. If not, it is condemned. Authority, by contrast, evaluates ambition by its orientation: What does it serve? Whom does it benefit? What constraints does it accept?

These questions reintroduce gravity into leadership. Authority slows decision-making where power accelerates it. It introduces reflection where efficiency demands speed. It acknowledges limits where power seeks expansion. This restraint is often misinterpreted as weakness in systems obsessed with growth. In reality, it is a source of durability.

History repeatedly confirms this. Leaders remembered with reverence are rarely those who exercised the greatest power, but those who embodied authority. Marcus Aurelius, who governed an empire, is remembered less for conquest than for restraint. Nelson Mandela’s authority derived not from force, but from moral clarity forged through suffering. Václav Havel, playwright, poet, and political dissident who went on to become the president of Czechoslovakia (1989-92), possessed little formal power for most of his life, exercised authority through integrity and truthfulness.

In each case, authority preceded power. When power eventually arrived, it was stabilized by legitimacy rather than fear.

This pattern has implications far beyond politics. In organizations, authority manifests as trust. It is felt when people believe that leadership decisions are grounded in principle rather than expediency. It appears when leaders take responsibility for failure rather than deflecting blame. It deepens when leaders are willing to sacrifice advantage for coherence.

Authority also reveals itself in silence. Leaders with authority do not need to dominate conversations. They listen. They create space. Their words carry weight precisely because they are not constant. In contrast, leaders reliant on power fill every silence, issue constant directives, and mistake activity for leadership.

The distinction between power and authority is therefore not merely historical or philosophical. It is intensely practical. It determines whether leadership generates resilience or fragility, meaning or cynicism, continuity or collapse.

Modern systems have become extraordinarily efficient at generating power. They are far less adept at cultivating authority. This imbalance is now reaching a critical point. Technological amplification, financial abstraction, and algorithmic governance have multiplied power while further distancing leaders from lived human consequences. Authority, already weakened, struggles to keep pace.

The answer is not nostalgia. It is integration.

Power is necessary. Leadership without power is often impotent. But power must be anchored in authority if it is to endure. Authority does not oppose effectiveness; it gives effectiveness meaning. It transforms leadership from a function into a vocation.

Recovering authority begins with inner work — the cultivation of self-awareness, ethical clarity, and humility. It requires leaders to confront uncomfortable truths about their motivations and attachments. It demands a willingness to be accountable not only for results, but for the human cost of achieving them.

Such work cannot be delegated. It cannot be automated. It cannot be reduced to frameworks alone. It unfolds gradually, through reflection, restraint, and the courage to align action with principle.

In a world saturated with power and starved of legitimacy, this recovery is not optional. It is the condition for sustainable leadership.

History does not remember those who accumulated the most power. It remembers those whose authority endured — because it was rooted in coherence, service, and truth.

That distinction, once understood, changes everything.