When Ambition Was Sacred: What Ancient Civilizations Understood About Success That We Don’t

Modern culture treats ambition as a purely personal force. It is framed as a private drive, an individual hunger for advancement, recognition, or achievement. We measure it in outcomes: wealth accumulated, status attained, influence expanded. Ambition, in this view, is morally neutral at best and morally suspect at worst — something to be indulged cautiously, restrained ethically, or justified retrospectively by results.

This framing would have been deeply alien to most ancient civilizations.

For much of human history, ambition was not regarded as a private appetite but as a cosmic responsibility. It was understood as a force that could either align the individual with the deeper order of the world or rupture that order entirely. Success was never evaluated solely by what one gained, but by what one served.

Ambition, in other words, was once sacred.

This did not mean that ancient societies rejected achievement, excellence, or greatness. On the contrary, they often revered them. But ambition was expected to be oriented — upward toward truth, justice, harmony, or the divine — rather than inward toward ego alone. When ambition lost this orientation, it was considered dangerous not only to the individual, but to the community and even the cosmos.

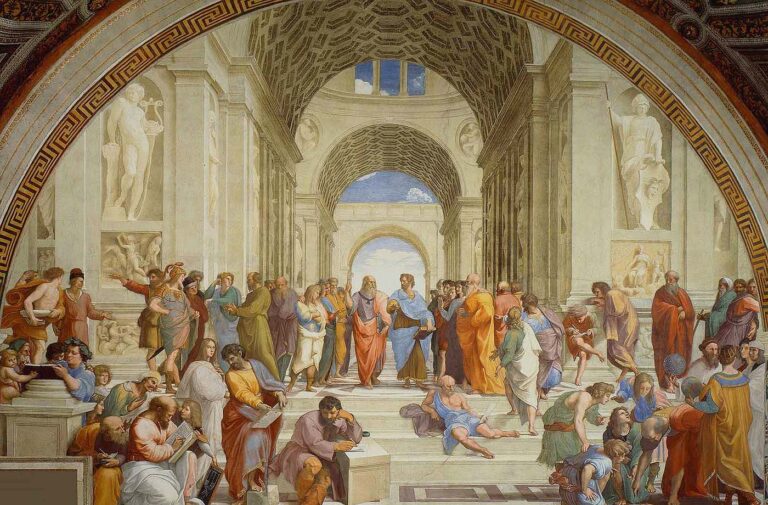

The ancient Greeks offer a clear starting point. In classical Athens of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, ambition was inseparable from the concept of aretē, often translated as virtue or excellence. To be ambitious was not merely to rise, but to rise well. Excellence was measured by the cultivation of character as much as by public achievement.

Plato, writing in the fourth century BCE during a period of political instability following the Peloponnesian War, was acutely aware of the destructive potential of misdirected ambition. In The Republic, he portrays the soul as divided into appetitive, spirited, and rational parts. Ambition (thymos) belongs to the spirited element — the source of courage, honor, and aspiration. When guided by reason, ambition becomes noble; when captured by appetite, it becomes tyrannical.

This psychology was not abstract theory. It was a diagnosis of social decay. Plato had witnessed how Athens’ ambitious leaders pursued power, prestige, and empire without moral restraint, leading ultimately to defeat, corruption, and the execution of his teacher Socrates. Ambition divorced from wisdom, he believed, was not progress but collapse.

Aristotle, Plato’s student, offered a more grounded vision. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he described megalopsychia — greatness of soul — as a virtue. The great-souled person seeks honor and achievement, but only insofar as they are deserved. Ambition becomes virtuous when it reflects a truthful understanding of one’s capacities and responsibilities. Excessive ambition (pleonexia), by contrast, is a form of injustice — the desire to have more than one’s share.

For Aristotle, success was inseparable from contribution to the polis, the civic community. Achievement that undermined social harmony was not success at all, regardless of how impressive it appeared. Ambition was evaluated by its effect on the whole.

This orientation was shared, with different language, by ancient Rome. In the Roman Republic of the first centuries BCE, ambition (ambitio) was viewed with deep ambivalence. On the one hand, Rome admired excellence, courage, and public service. On the other, unrestrained ambition was feared as a corrosive force that could destroy the republic.

Cicero, the Roman statesman and philosopher writing during the Republic’s final crisis, warned repeatedly against ambition severed from duty. In De Officiis, he argued that honor arises from service to the common good, not from self-promotion. The very word ambitio carried negative connotations, implying the act of “going around” soliciting favor for personal gain.

Rome’s greatest heroes were not those who amassed wealth, but those who embodied virtus — courage, discipline, and sacrifice in service of Rome. When ambition shifted from service to self-enrichment, the republic began to fracture. Julius Caesar’s ascent was not merely a political event; it was a moral rupture, signaling that ambition had overwhelmed restraint.

Beyond the Greco-Roman world, similar patterns appear.

In ancient India, ambition was understood within the framework of dharma — the moral and cosmic order governing individual and social life. Success was legitimate only when aligned with one’s duty and stage of life. The Bhagavad Gita, composed between roughly the fifth and second centuries BCE, addresses ambition directly. Krishna counsels Arjuna to act with full commitment, yet without attachment to personal gain. Action oriented toward ego binds the soul; action aligned with duty liberates it.

Here, ambition is neither suppressed nor indulged. It is consecrated.

Ancient Chinese philosophy articulated this balance with striking clarity. Confucius, living in the sixth and fifth centuries BCE during a period of social fragmentation known as the Spring and Autumn period, emphasized self-cultivation as the foundation of legitimate ambition. Success was measured not by domination, but by harmony — within the self, the family, the state, and the cosmos.

Ambition unmoored from virtue was considered a threat to social order. The ideal leader governed through moral example, not force. Authority flowed naturally from integrity. Ambition, when aligned with ren (humaneness) and li (proper conduct), strengthened society. When misaligned, it produced chaos.

Even ancient mythologies encode this lesson. The Greek myths of Icarus, Tantalus, and King Midas are not condemnations of aspiration itself, but warnings against ambition that ignores limits. To reach beyond one’s place without wisdom is to invite destruction. Ambition was expected to be disciplined by humility and reverence for forces greater than oneself.

What unites these traditions is a shared assumption: ambition is not a private right but a moral force. It shapes not only individual destiny, but collective fate. Because of this, ambition required initiation, formation, and restraint. Leaders were trained, tested, and often subjected to periods of asceticism or service before assuming authority.

Modern culture has largely abandoned this view.

The rise of individualism, capitalism, and technological acceleration reframed ambition as a personal project. Success became measurable primarily in external terms: income, rank, visibility, and growth. Ethical considerations were gradually relegated to compliance frameworks rather than internalized virtues. Ambition became something to be optimized, not oriented.

This shift has produced extraordinary innovation and prosperity. It has also produced profound dislocation. When ambition loses its sacred dimension, it becomes restless. It can never be satisfied, because it is no longer anchored to meaning. Achievement multiplies, but fulfillment recedes.

This is the paradox many high achievers now face. They have done everything modern culture promised would bring satisfaction — and yet something essential remains missing. The problem is not ambition itself, but its desacralization.

Ambition was never meant to be hollow. It was meant to be a bridge between the individual and the larger order of life.

The consequences of this shift are now becoming visible across professional and cultural life. When ambition is stripped of its sacred or moral orientation, it becomes purely extractive. It seeks more—more recognition, more control, more validation—but without a coherent sense of why. This produces what many successful individuals experience privately but rarely articulate publicly: a sense of acceleration without arrival.

Ancient societies anticipated this condition. They understood that ambition, when unchecked by meaning, eventually turns against the individual. The Greeks called this hubris—the overreaching pride that invites downfall. Hubris was not arrogance in the modern sense; it was a metaphysical error, a failure to recognize one’s place within a larger order. Tragedy followed not because the gods were vindictive, but because imbalance inevitably corrects itself.

This corrective principle appears again and again in ancient thought. In Egypt, leadership was understood through Ma’at, the principle of cosmic balance, truth, and justice. Pharaohs were not merely rulers but stewards of harmony between heaven and earth. Success was measured by the maintenance of balance, not by expansion alone. When rulers violated Ma’at, disorder (isfet) followed—socially, economically, and spiritually.

In the ancient Near East, kings were often depicted receiving authority from the divine, not as a reward, but as a burden. Their legitimacy depended on justice for the poor, restraint in power, and reverence for forces beyond themselves. Ambition, here, was inseparable from responsibility. To rise was to serve.

These frameworks did not eliminate corruption or failure, but they provided a shared moral grammar. Leaders understood that ambition required justification beyond personal desire. The community, the ancestors, the gods, or the cosmic order served as mirrors against which ambition was measured.

Modern leadership lacks such mirrors.

In their absence, ambition becomes self-referential. It feeds on comparison rather than contribution. Success is validated externally—through metrics, applause, or market dominance—rather than internally through coherence or alignment. This produces leaders who appear confident yet remain perpetually anxious, driven yet dissatisfied.

The psychological cost is significant. Contemporary research on burnout, moral injury, and executive isolation echoes ancient warnings in modern language. When ambition is disconnected from purpose, it exhausts rather than ennobles. It demands constant motion because stillness would expose its emptiness.

This is why many high-performing individuals eventually reach what has been described as the “second mountain”—a point at which external success no longer compensates for inner disquiet. Though the language is modern, the experience is ancient. It is the moment when ambition asks to be reoriented rather than intensified.

Ancient traditions anticipated this transition and built pathways for it. Initiatory rites, periods of retreat, philosophical study, and ascetic practices were not marginal curiosities; they were mechanisms for refining ambition. Before one could lead, one had to confront oneself.

Consider the Eleusinian Mysteries of ancient Greece, practiced for nearly two millennia. Participation was restricted, preparation was required, and the experience was said to transform one’s relationship to life, death, and purpose. Though details remain secret, ancient sources suggest that the Mysteries offered a reorientation of desire—from acquisition toward reverence.

Similarly, in ancient India, the four stages of life (ashramas) explicitly recognized that ambition must evolve. The householder stage encouraged achievement and responsibility, but later stages emphasized detachment, wisdom, and service. Ambition was not extinguished; it was transmuted.

Modern culture rarely offers such transitions. Instead, it encourages indefinite striving. Leaders are expected to maintain peak performance indefinitely, without corresponding deepening of meaning. The result is a culture of perpetual adolescence—powerful, capable, and uninitiated.

To say that ambition was once sacred is not to romanticize the past. Ancient societies were often harsh, unequal, and violent. But they possessed an insight modern systems have neglected: ambition shapes the soul. If it is not consciously oriented, it will unconsciously dominate.

Re-sacralizing ambition does not require adopting ancient beliefs wholesale. It requires recovering the underlying principle: success must serve something larger than the self. This “something” need not be religious in a narrow sense. It may be ethical, humanistic, ecological, or spiritual. What matters is that ambition is accountable to a higher horizon.

When ambition is reoriented in this way, leadership changes qualitatively. Decisions are no longer driven solely by advantage, but by impact. Power is exercised with restraint. Success becomes a means rather than an end.

This reorientation also restores dignity to effort. When ambition is sacred, work is not merely instrumental; it is expressive. It becomes a way of participating in the unfolding of meaning rather than a race toward accumulation. Leaders who rediscover this orientation often report a paradoxical effect: they become less driven by outcomes, yet more effective. Their clarity stabilizes others. Their presence invites trust.

In times of uncertainty and transition, societies instinctively seek such leaders. History shows that periods of upheaval are also periods of moral reckoning. The collapse of old frameworks creates space for new forms of legitimacy. Authority begins to flow not to those who promise control, but to those who embody coherence.

Our own era is no exception. Technological acceleration, environmental instability, and social fragmentation have exposed the limitations of ambition defined purely by growth. The question is no longer whether we can achieve more, but whether we can orient achievement wisely.

Ancient civilizations would recognize this moment. They would see it not as a failure of ambition, but as its initiation.

Ambition was never meant to be abandoned. It was meant to be consecrated—to become a force that lifts rather than consumes, that integrates rather than divides. When ambition remembers its sacred dimension, success regains its depth, leadership recovers its legitimacy, and progress acquires meaning.

What we have forgotten is not how to succeed, but why success mattered in the first place.