The Second Mountain Is Older Than We Think — A Journey Through Philosophy, Faith, and Leadership

In recent years, the phrase “the second mountain” has entered popular discourse as a way of describing a transition many successful people experience later in life. The term is most closely associated with David Brooks, an American journalist and social commentator writing in the early twenty-first century, who used it to describe the movement from achievement-driven success toward a more relational, service-oriented way of living. In this contemporary framing, the first mountain represents ambition, status, and accomplishment; the second represents meaning, commitment, and contribution.

This modern articulation has resonated widely, particularly among professionals who have reached conventional markers of success yet feel an unresolved restlessness beneath the surface. It gives language to an experience that is both common and difficult to articulate.

Yet the experience itself is far older than its modern name.

Long before it was framed as a second mountain, this transition was understood as a fundamental passage in human development — one that ancient philosophies, religious traditions, and initiatory systems placed at the very center of their understanding of a fulfilled life. What is often treated today as a late-life pivot or personal reinvention was once recognized as a necessary evolution of consciousness, leadership, and responsibility.

The difference between contemporary usage and the perspective explored here is therefore not one of disagreement, but of depth and lineage. The second mountain is not a modern insight responding to recent social conditions; it is an ancient pattern temporarily obscured by the particularities of modern success culture.

To see this, we must step back from the language of career arcs and self-actualization and enter a much older conversation — one concerned not with optimization, but with transformation.

Ancient philosophies did not conceive of life as a single, continuous ascent. They understood it as a series of qualitative shifts, each requiring the relinquishment of previous identities. Advancement was not linear; it was initiatory. One did not simply accumulate more of the same. One became something different.

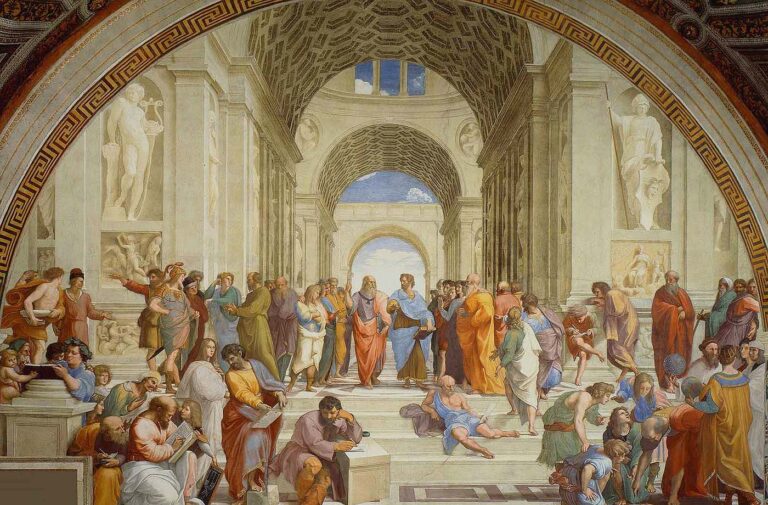

In classical Greece of the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, this idea appeared in philosophical form. Plato, writing in the aftermath of political turmoil and the execution of Socrates, described human development as a gradual turning of the soul. In The Republic, the famous allegory of the cave depicts individuals initially striving for status and recognition within the shadows of social life, before undergoing a painful reorientation toward truth. The ascent out of the cave is not a reward for ambition; it is a consequence of disillusionment with it.

The individual who returns to the cave after this ascent does not do so to compete, but to serve. Leadership, in this framing, emerges only after ambition has been purified by insight. The second ascent is not about personal fulfillment, but about responsibility.

Aristotle, writing slightly later in the fourth century BCE, offered a more practical articulation. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he observed that happiness (eudaimonia) cannot be achieved through honor, wealth, or pleasure alone. These goods are incomplete because they depend on external validation. True flourishing, he argued, arises from the exercise of virtue in accordance with reason over a complete life.

Implicit in this argument is a developmental sequence. Early life may rightly pursue recognition and achievement, but maturity demands a different orientation. The virtuous life is not a retreat from the world, but a re-engagement with it from a deeper foundation.

Roman philosophy absorbed and extended these ideas. Stoic thinkers such as Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, writing in the first and second centuries CE during the height of the Roman Empire, addressed readers who possessed power, wealth, and status — and yet felt internally unsteady. In Letters from a Stoic and Meditations, respectively, they urged a turning inward, away from dependence on external success and toward mastery of judgment, desire, and fear.

For the Stoics, the first mountain was represented by attachment to fortune. The second was reached when one learned to act in accordance with reason and nature, independent of praise or blame. Leadership, once again, was transformed by this shift. The wise leader governed not from appetite or fear, but from inner freedom.

Religious traditions encode the same pattern, often more explicitly. In the Hindu philosophical tradition, particularly as expressed in texts such as the Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita, life is understood as a movement from action driven by desire (kama) toward action grounded in duty (dharma) and ultimately toward liberation (moksha). The householder’s life of responsibility and achievement is honored, but it is not the final word. Fulfillment requires transcendence of ego-bound striving.

Buddhist philosophy, emerging in the fifth century BCE through the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, the Buddha, frames this transition as awakening from attachment. Worldly success, while not condemned, is recognized as insufficient to resolve suffering. Insight arises when craving gives way to compassion and wisdom. Leadership in Buddhist societies was ideally exercised by those who had undergone this inner shift.

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the same movement appears through a different lens. Biblical narratives repeatedly depict figures who achieve prominence, only to be stripped of it before assuming true leadership. Moses flees into the desert before returning as a guide for his people. King David’s authority is forged through suffering and repentance, not triumph alone. In the New Testament, Jesus explicitly rejects worldly power, redefining greatness as service.

Early Christian monasticism systematized this pattern. Figures such as Anthony the Great in the third and fourth centuries CE withdrew from public life not to escape responsibility, but to confront ambition at its roots. Their authority emerged precisely because they had renounced the first mountain. When they later advised emperors and bishops, their words carried weight because they had nothing to gain.

Across these traditions, a consistent insight emerges: the second mountain is not a choice among many, but a necessary transformation. The first mountain — the pursuit of success, security, and recognition — builds capacity, discipline, and skill. But it cannot sustain meaning indefinitely. At some point, it collapses under its own weight.

Modern culture, however, has obscured this passage. By treating success as an endpoint rather than a stage, it leaves individuals stranded on the first mountain, encouraged to climb higher when what is required is a change of direction.

This is why the contemporary language of the second mountain resonates so strongly. It gives voice to an ancient transition that modern systems have failed to ritualize, guide, or honor. Yet without historical grounding, it risks being misunderstood as a lifestyle choice rather than a developmental necessity.

The second mountain is not a retreat from ambition. It is ambition transformed.

What distinguishes the second mountain from a simple midlife adjustment is that it is not primarily about changing circumstances, but about changing orientation. The first mountain asks, “How do I succeed?” The second asks, “To what end?” This question is not philosophical abstraction; it exerts pressure on every decision a leader makes once the initial rewards of success have lost their power to satisfy.

Ancient traditions understood that this question could not be answered intellectually alone. It required confrontation with impermanence, loss, and limitation. This is why so many formative narratives include exile, retreat, illness, or failure. These experiences were not viewed as interruptions to the path, but as initiations into its deeper meaning.

In classical philosophy, this initiation was framed as a reordering of desire. Plato described it as turning the soul toward what is real. Aristotle understood it as aligning desire with reason. The Stoics called it freedom from false attachments. In each case, the movement is away from dependence on external validation and toward inner coherence.

This shift has direct implications for leadership. Leaders operating from the first mountain tend to measure success by expansion: larger teams, greater influence, higher valuation, broader reach. These are not inherently problematic, but they are insufficient. When expansion becomes the sole metric, leaders become trapped by the very systems they built. Growth demands constant acceleration. Authority becomes fragile because it rests on continued performance rather than trust.

The second mountain introduces a different metric: depth. Depth of judgment. Depth of responsibility. Depth of presence. Leadership from this orientation is quieter but more resilient. It does not require constant reinforcement because it is anchored in clarity rather than ambition alone.

History offers countless examples of leaders who reached this transition and responded differently. Some clung to the first mountain, intensifying control as meaning slipped away. Others underwent a genuine reorientation, emerging with authority that transcended position.

Marcus Aurelius, Roman emperor in the second century CE, is emblematic of the latter. Though he possessed extraordinary power, his Meditations reveal a man deeply suspicious of ambition for its own sake. Writing privately amid war and plague, he reminded himself repeatedly of impermanence, humility, and duty. His authority endured not because of spectacle or conquest, but because he governed with restraint and self-knowledge.

By contrast, later emperors who pursued glory without inner discipline accelerated Rome’s decline. Their ambition remained fixed on the first mountain even as the terrain beneath them eroded.

The same pattern appears in modern contexts. Leaders who reach the second mountain often do so through disillusionment rather than intention. They discover that the strategies that brought success no longer bring peace. Their competence remains intact, but their motivation shifts. They begin to ask questions modern leadership culture rarely encourages: What am I willing to stand for? What legacy am I actually building? What happens when I am no longer useful?

These questions are unsettling precisely because they cannot be answered by strategy alone. They require a confrontation with identity. On the first mountain, identity is constructed through roles, titles, and achievements. On the second, identity is stripped back to essence.

This stripping back of identity is often accompanied by grief. Ancient traditions did not shy away from this. The death of a former self was recognized as a prerequisite for transformation. Initiatory rites across cultures symbolized this death explicitly, marking the passage from one mode of being to another. Modern culture, by contrast, treats grief as pathology rather than passage, leaving individuals to navigate this transition without guidance.

The result is a proliferation of partial awakenings. People sense the need for change but lack a framework to integrate it. Some retreat into cynicism. Others seek distraction. Still others attempt to spiritualize ambition without relinquishing its core attachments. The second mountain becomes aesthetic rather than transformative.

Yet when the transition is genuine, its effects are unmistakable. Leaders who cross this threshold report a paradoxical combination of increased clarity and reduced urgency. They become less reactive, more discerning. Their decisions are informed not only by outcomes, but by consequences. Power, when exercised, is exercised with care.

This does not make leadership easier. In some respects, it becomes more demanding. The second mountain removes the comforting illusion that success alone justifies action. It requires leaders to hold complexity, tolerate ambiguity, and accept responsibility without the reassurance of applause.

But it also restores meaning. Work becomes an expression of values rather than a contest for validation. Influence becomes a means of stewardship rather than dominance. Authority deepens because it is no longer dependent on constant reinforcement.

Modern organizations are quietly hungry for this form of leadership. In environments saturated with information and performance metrics, people crave coherence. They respond instinctively to leaders whose ambition has been tempered by insight. Such leaders create psychological safety not through policy, but through presence.

The ancient world understood this intuitively. Leadership was not merely a function of intelligence or strength, but of inner alignment. Those who had crossed the second mountain were entrusted with greater responsibility precisely because they had less to prove.

Reframing the second mountain in this way allows us to reclaim it from trendiness and return it to its rightful place as a universal human passage. It is not a lifestyle upgrade, nor a retreat from success. It is the maturation of ambition itself.

The tragedy of modern leadership is not that too few people climb the first mountain. It is that too few are prepared for what comes next.

When ambition remains fixed on ascent alone, success becomes a burden rather than a gift. When ambition is reoriented toward service, coherence, and responsibility, leadership acquires depth.

The second mountain has always been there. It waits patiently, not for failure, but for readiness.

Those who answer its call do not abandon the world. They return to it — changed, steadied, and capable of leading in ways that power alone never could.