The Leaders Who Changed History Were Not the Most Efficient — They Were the Most Awake

Modern leadership culture is obsessed with efficiency.

We measure output per hour, optimize workflows, compress timelines, automate decisions, and celebrate speed as a virtue in itself. Leaders are praised for doing more with less, scaling faster, and eliminating friction wherever it appears. Efficiency has become synonymous with competence. To be inefficient is to be indulgent, outdated, or weak.

History tells a different story.

The leaders who most profoundly shaped civilizations were rarely the most efficient by contemporary standards. They were not always decisive in the short term, nor relentlessly productive, nor obsessed with optimization. What distinguished them was something harder to quantify and easier to overlook: awareness. They perceived context deeply. They sensed timing. They understood human nature. They acted not merely from calculation, but from presence.

Efficiency moves systems. Awareness moves civilizations.

Consider the difference between a manager and a statesman. The manager focuses on execution: inputs, outputs, constraints. The statesman operates within a wider field: culture, psychology, moral legitimacy, and historical consequence. Efficiency serves the immediate objective. Awareness serves the long arc.

This distinction has existed for as long as leadership itself.

In ancient China, during the Warring States period (roughly the fifth to third centuries BCE), competing kingdoms raced to centralize power, standardize law, and streamline administration. Many rulers pursued ruthless efficiency: uniform punishments, rigid hierarchies, rapid mobilization. The Legalist school of thought, exemplified by thinkers like Han Feizi, argued that order arose from strict laws applied mechanically, without regard for moral nuance. The system mattered more than the person.

Yet the civilization that endured was shaped not by Legalist efficiency alone, but by Confucian awareness. Confucius (sixth–fifth century BCE) emphasized ren—humaneness—and li—ritual propriety—not as inefficiencies, but as the invisible structures that held society together. He understood that leadership was not merely about enforcing behavior, but about cultivating character. A ruler who lacked self-awareness could impose order, but not harmony.

This is a recurring historical pattern: efficiency builds empires; awareness sustains them.

The Roman Empire perfected administration, logistics, and law. Its roads were marvels of efficiency. Its legions were disciplined machines. Yet Rome’s most enduring leaders were remembered not for speed, but for judgment. Marcus Aurelius, emperor in the second century CE, governed at the height of Roman power, yet his private reflections in his Meditations reveal a man deeply attentive to his inner life. He returned again and again to restraint, humility, and the limits of control. His leadership was not driven by urgency, but by orientation.

Marcus Aurelius was not the most efficient ruler Rome produced. He was among the most awake.

Awareness, unlike efficiency, resists metrics. It cannot be captured in dashboards or key performance indicators. It expresses itself as timing rather than speed, as proportion rather than volume. An aware leader may delay action not because they are indecisive, but because they sense that premature movement would fracture trust, escalate conflict, or foreclose better outcomes.

Efficiency seeks to eliminate friction. Awareness asks whether friction is meaningful.

Many pivotal moments in history hinged on leaders who refused to act efficiently in the narrow sense. Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president of the United States during the Civil War, is often criticized by modern commentators for his slowness. He hesitated. He tolerated dissent. He revised positions. Yet this “inefficiency” was in fact attentiveness to a deeply divided moral and political landscape. Lincoln understood that preserving the Union required not only military victory, but psychological and symbolic legitimacy. His leadership unfolded at the pace of conscience, not convenience.

His Second Inaugural Address, delivered in 1865, is striking for its absence of triumphalism. “With malice toward none; with charity for all,” he framed victory as responsibility, not vindication. This was not efficient rhetoric. It was conscious leadership. It aimed not to win the war again, but to heal the conditions that made the war possible.

Contrast this with leaders who optimized for dominance alone. They often achieved rapid consolidation, only to preside over brittle systems that collapsed under pressure. Efficiency without awareness accelerates decline.

The modern corporate world mirrors this dynamic with uncanny precision. Organizations optimize processes, flatten hierarchies, and automate decision-making, often at the expense of context and human nuance. Leaders are rewarded for decisiveness even when decisions are misaligned with deeper cultural realities. The result is a proliferation of technically successful but spiritually exhausted institutions.

Awareness, by contrast, requires the leader to remain porous to reality. It demands the capacity to notice subtle shifts: morale declining before metrics register it; ethical erosion before scandals erupt; mission drift before purpose is lost. This kind of perception cannot be rushed.

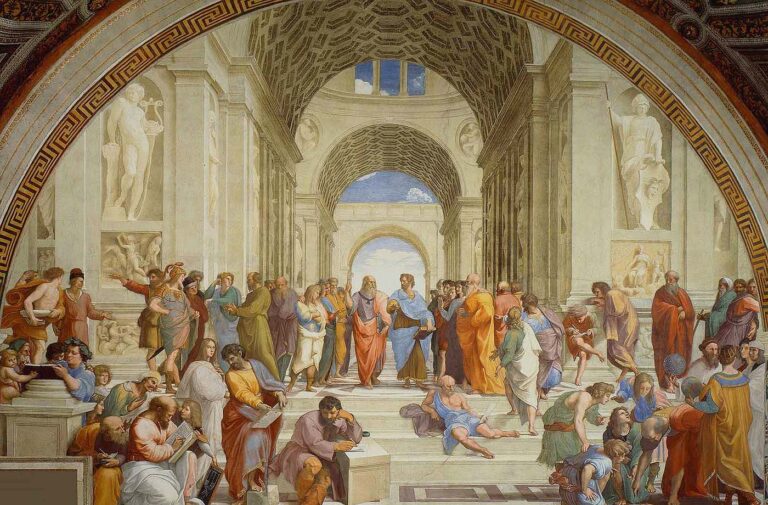

Philosophers have long warned against mistaking speed for wisdom. Aristotle, writing in the fourth century BCE, distinguished between techne—technical skill—and phronesis—practical wisdom. Techne concerns means; phronesis concerns ends. One can be extremely efficient at doing the wrong thing. Awareness ensures that efficiency is oriented toward what actually matters.

This distinction becomes critical as leaders gain power. Early in a career, efficiency often compensates for limited authority. Later, awareness becomes indispensable. Power amplifies consequences. An efficient misjudgment at scale can be catastrophic.

History’s most destructive leaders were often highly efficient. They mobilized quickly, centralized authority, eliminated opposition, and executed plans with precision. What they lacked was not intelligence, but awareness—of human complexity, moral limits, and long-term consequences. Efficiency without awareness becomes brutality.

By contrast, transformative leaders often appeared slow, contemplative, or even obstructive to their contemporaries. Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian independence leader of the early twentieth century, frustrated allies and adversaries alike with his insistence on nonviolent resistance. From a purely operational standpoint, his methods were inefficient. They required patience, restraint, and moral discipline. Yet Gandhi understood something his opponents did not: legitimacy outlasts force. Awareness of human psychology and ethical resonance enabled him to mobilize millions without weapons.

Awareness also operates inwardly. Leaders who changed history were often those who cultivated inner stillness amid external chaos. This inner stability allowed them to act without being reactive, to respond rather than merely react. They were not driven by impulse or fear, but by orientation.

Modern neuroscience echoes this insight. States of calm attentiveness enhance cognitive flexibility, empathy, and ethical reasoning. Chronic urgency narrows perception. Leaders trapped in constant acceleration lose the capacity to see beyond immediate threats. Awareness expands the field of vision.

Efficiency thrives on urgency. Awareness requires space.

This does not mean that aware leaders are passive or indecisive. On the contrary, their actions often carry unusual clarity and force precisely because they are not rushed. When they act, it is from alignment rather than anxiety. Their decisions integrate intellect, intuition, and moral sense.

One of the great myths of modern leadership is that awareness slows progress. History suggests the opposite: awareness prevents false progress. It reduces the need for correction, repair, and apology. It aligns action with reality before consequences become irreversible.

The leaders who changed history were not those who moved fastest, but those who saw deepest.

They recognized that leadership is not a race, but a relationship—with people, with time, and with meaning. Efficiency is a tool. Awareness is a stance. When the two are aligned, leadership becomes generative rather than extractive.

What modern culture often forgets is that efficiency is contextual. It is valuable only when guided by awareness. Without that guidance, it becomes an accelerant poured onto unresolved tensions. Awareness does not reject efficiency; it places it in service to something larger.

The question facing today’s leaders is not whether to be efficient, but whether they are awake enough to know when efficiency serves—and when it undermines—the very outcomes they seek.

Awareness, then, is not a personality trait. It is a discipline.

It requires the leader to remain awake to multiple layers of reality simultaneously: the external environment, the internal state, the unspoken dynamics within groups, and the long-term consequences of present actions. This is demanding work. It cannot be automated. It cannot be delegated. And it often conflicts with the pressure to appear decisive, confident, and constantly in motion.

One reason awareness has fallen out of favor in modern leadership culture is that it does not perform well in quarterly reporting cycles. Efficiency produces immediate, visible outputs. Awareness produces coherence—something felt before it is measured, sensed before it is named. In systems driven by speed and competition, coherence can look suspiciously like hesitation.

Yet history suggests that coherence is precisely what allows leadership to endure.

The most influential spiritual and philosophical leaders were rarely the most efficient organizers. he Athenian philosopher Socrates wrote nothing, built no institution, and held no formal power. From an efficiency standpoint, he was useless. From an awareness standpoint, he was revolutionary. His method—persistent questioning—slowed conversations down. It disrupted certainty. It forced people to examine their assumptions. The Athenians eventually executed him, not because he was ineffective, but because his awareness threatened the efficient functioning of unexamined authority.

The legacy of Socrates did not lie in systems or structures, but in orientation. He shifted the axis of leadership inward, insisting that self-knowledge precede governance. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” he famously declared—an assertion that remains deeply inconvenient for leaders who prefer momentum over reflection.

This tension between awareness and efficiency reappears in religious leadership as well. Jesus of Nazareth in Roman-occupied Judea, did not build a bureaucratic organization during his lifetime. His leadership was inefficient by design. He spent time with individuals. He told stories rather than issuing policies. He withdrew frequently for solitude. Yet his influence reshaped ethical frameworks across civilizations for millennia. His authority did not arise from speed or scale, but from presence.

The same pattern holds in the Islamic tradition, where Muhammad, the seventh-century prophet and statesman, balanced decisive action with extended periods of contemplation. Islamic historical sources emphasize his retreats for reflection and his attentiveness to communal harmony. The early Islamic community was not built solely on conquest, but on relational cohesion and ethical guidance. Awareness anchored action.

What unites these figures is not ideology, but orientation. They acted from a place of alignment rather than urgency. Their leadership emerged from clarity of being, not merely clarity of plan.

Modern leadership education rarely addresses this dimension explicitly. It teaches frameworks, competencies, and tools, but often neglects the inner conditions from which these tools are deployed. The assumption is that effectiveness is neutral—that a capable leader will naturally use power well. History contradicts this assumption relentlessly.

Power without awareness accelerates fragmentation. Influence without presence breeds alienation. Efficiency without wisdom produces brittle systems that shatter under stress.

In organizational life, this often manifests as cultures optimized for performance but devoid of meaning. Employees deliver results but disengage internally. Leaders meet targets but feel strangely empty. Burnout proliferates not because people work too hard, but because they work without coherence between values and actions.

Aware leaders notice this early. They sense when an organization’s metrics are improving while its morale erodes. They understand that culture cannot be fixed through policy alone. They recognize that trust, once lost, cannot be optimized back into existence.

Awareness also transforms how leaders relate to time. Efficient leaders are future-oriented in a narrow sense: deadlines, forecasts, projections. Aware leaders hold a wider temporal horizon. They respect rhythm and recovery. They understand that growth requires integration, not constant expansion. This temporal awareness is why some leaders choose to pause growth deliberately, to consolidate learning, strengthen culture, or restore balance.

Such pauses are often misinterpreted as weakness. In reality, they reflect confidence grounded in clarity rather than anxiety.

The difference becomes most apparent during crisis. Efficient systems often collapse when conditions deviate from expectations. Aware leaders, by contrast, adapt more fluidly because they are not rigidly attached to predefined outcomes. They respond to what is, not to what should have been. Their decisions may appear slower initially, but they tend to be more resilient.

The Japanese concept of ma—the space between things—captures this well. In traditional Japanese aesthetics and leadership, pauses are not empty; they are generative. Awareness lives in these spaces. Efficiency seeks to eliminate them.

Modern neuroscience reinforces this insight. Research on decision-making under stress shows that constant urgency degrades executive function. Reflection restores it. Leaders who cultivate awareness—through contemplation, embodied practices, or disciplined self-observation—maintain cognitive flexibility under pressure. They are less reactive, more discerning.

This is not mystical. It is physiological.

And yet, awareness remains undervalued precisely because it resists commodification. You cannot scale presence the way you scale processes. You cannot outsource conscience. Leadership culture prefers what can be replicated, even when what is needed is what can be embodied.

The leaders who changed history understood this intuitively. They did not confuse motion with meaning. They did not mistake speed for direction. They were willing to appear inefficient in the short term to remain aligned in the long term.

This is why they are remembered.

Efficiency leaves no trace beyond its outputs. Awareness leaves a lineage. It shapes norms, values, and expectations that outlast individual tenures. It influences how people treat one another when authority is absent. It becomes culture.

The modern world does not need less efficiency. It needs efficiency re-anchored in awareness. Leaders who can integrate both—who move decisively without losing depth, who act swiftly without abandoning wisdom—will shape the next era of leadership.

The question is not whether efficiency matters. It does.

The deeper question is whether efficiency is serving awareness—or replacing it.

History’s verdict is clear. The leaders who altered the course of civilizations were not those who optimized hardest, but those who saw most clearly. They understood that leadership is not about doing more, faster. It is about being more awake, more present, and more responsible with the power entrusted to them.

In the end, awareness is not an alternative to effectiveness. It is the condition that makes effectiveness humane, sustainable, and worthy of trust.